Most of the energy that hits a solar panel is wasted. Energy technology researcher Peng Wang told IE that less than 20 percent of the energy that hits a solar panel gets turned into electricity.

The rest is turned into heat, which can cause the panel to become even less efficient.

Researchers have spent decades figuring out how to squeeze more electricity out of solar panels, coming up with solutions like harvesting energy from more colors of light by replacing silicon with quantum dots.

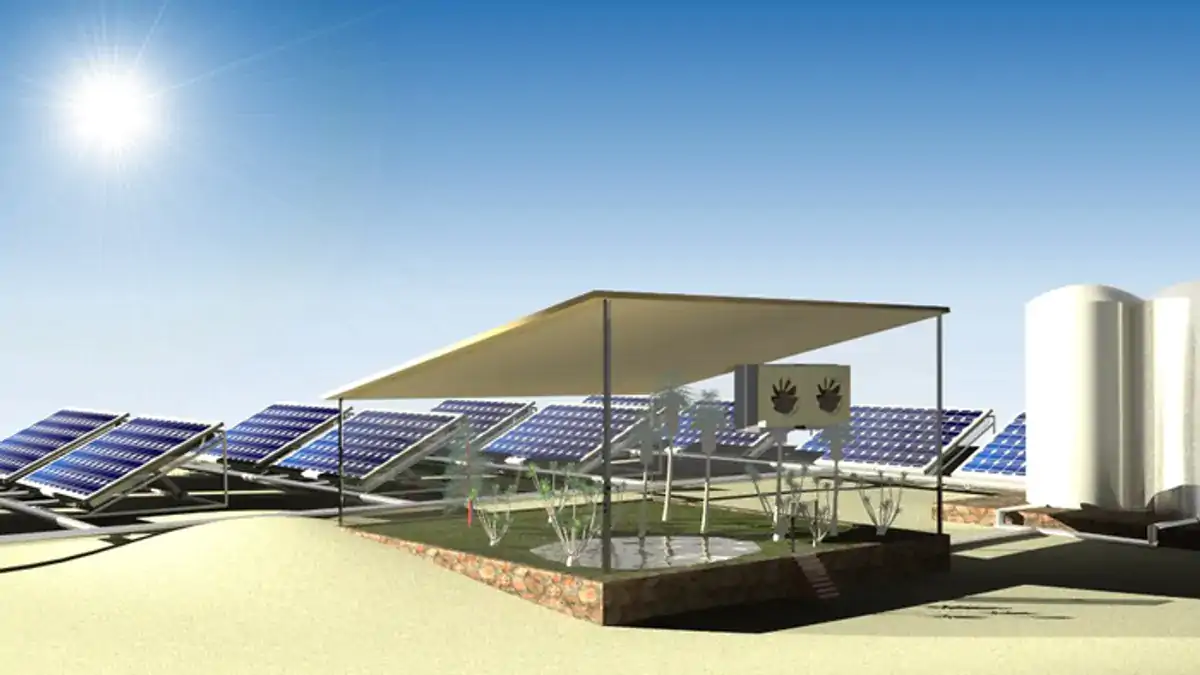

Wang's team at King Abdullah University in Saudi Arabia takes a different approach. They found a way to use the waste heat.

Their system, described in a paper published this week in the academic journal Cell Reports Physical Science, uses the otherwise unusable energy to pull water from the desert air.

Saudi Arabia offered Wang tons of funding — and inspiration

Wang earned his Ph.D. from the University of California Santa Barbara in 2009, just a few months before the grand opening of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

An NPR journalist reporting from the event called the university the king's "pet project" and described it as "a graduate-level institution that will research how to harness solar power, desalinate water, and genetically alter plants to survive in the harsh desert."

The university, funded by a $10 billion endowment, made big promises to lure Wang.

"That [was] the first time I'd heard [the words] 'unlimited funding,'" he says.

As the researcher got to know his new home, he was struck by what he saw in rural parts of Saudi Arabia.

"As you move away from the city and get into small villages, water is very challenging because the only way to [get it] is by transporting it by truck."

The realization led him to adjust his research program and search off-grid ways to create water, food, and energy. He says he wants to make sure those who aren't well-served by the centralized infrastructure can "have a decent life."

Water is everywhere, but billions thirst

It should go without saying that fundamental resource scarcity is a massive global problem, but it can be an easy one for many of us to overlook. The U.N. says more than two billion people lack access to safely managed drinking water services. More than 2.3 billion people (or 30 percent of the global population) lacked year-round access to adequate food.

And yet, water — in the form of vapor — is everywhere all the time. Thirty-seven trillion tons of it cycle through the atmosphere every year. The problem is that transforming water vapor into liquid water, a process called atmospheric water harvesting, is hard to do at scale.

Less than a year ago, researchers working at X, a corporate research lab owned by Google parent company Alphabet, published a paper in Nature arguing that with a little technological progress, atmospheric water harvesting could provide clean water to roughly a billion people.

The device Peng's team invented might contribute to that lofty goal.

Say goodbye to "waste heat"

The invention relies on a type of hydrogel that Peng's team has been working on for several years. It has two key elements. First, there's a hygroscopic salt, which wants very much to attract water molecules.

Wang says if you put a pinch of the stuff on a table, you'd soon be "left with a pool of water" because the salt is "so powerful in gaining water from air that it would [have dissolved itself] in the water it harvested."

The second element is an "interconnected polymer structure" that's highly porous, leaving plenty of room for water molecules to collect inside.

Put the two pieces together, and they act like a self-soaking sponge.

"Water [molecules] get into the matrix and [come into] contact with the salts, and then the water is formed inside the hydrogel," he says.

That's hardly remarkable in and of itself. Several materials — including zeolite, a mineral made of silicon, aluminum, and oxygen — have similar water-attracting properties.

The problem is that those materials aren't very practical when it comes to getting the water back out. Zeolite has to get very warm — a home oven might be able to get hot enough — before it releases the water molecules locked away inside.

Wang's hydrogel is special because it lets go of its water molecules at much lower temperatures. It turns out that the excess heat from the back of a solar panel, which can be 50 degrees higher than the air temperature, is plenty of energy to do the trick.

The invention is a win-win addition to solar panels

Peng's invention can work in two different ways. In cooling mode, the hydrogel is exposed to the open air all the time. During the night, the material collects water molecules. As the sun heats up the solar panel the next day, the molecules evaporate, taking excess heat energy with them.

"It's how the human body reduces temperature by sweating," Wang says. The cooling mode doesn't collect any water, but it can increase the electrical output of a solar panel by roughly 10 percent.

In crop production mode, the hydrogel is exposed to the air at night and sealed off during the day. That way, the water escaping the hydrogel can be put to use.

"The evaporated vapor [is] condensed inside a chamber," Wang said.

As it stands now, the system doesn't create a lot of water, just enough to grow some spinach. Wang says that's because "it's the first proof of concept."

"We have a long way to go because the performance of the system was not optimized in the paper that we just published… Hopefully, very soon, there can be some real impact."

That impact might occur on solar farms, which are often located in places where water is an especially precious resource. But that's not the only way this technology could be deployed. People who live in villages and small communities across the world can benefit from having their own technologies that simultaneously create two vital resources at the same time.

The Sun "can give us a lot of things"

"You cannot rely on large-scale water production," Wang says, especially when there aren't pipes to send it to the people who need it. If nothing else, transporting water that way is costly.

He knows a thing or two about living off the grid. The researcher grew up in the 1970s and 80s in a village of about 400 people in China. While his family didn't worry too much about running out of water — they had a well — neighbors living across the border in the next province weren't so lucky.

They gathered water from the atmosphere in a more traditional way, collecting snow in the winter and storing it underground as a water source during the dry summer months.

Wang says his high-tech solution will only be a game-changer for people in the "very least developed countries" if they can afford it.

That's why his team is trying to make it cheap to build. He hopes that governments and NGOs can offer support, too. But as it stands now, the path forward isn't entirely clear.

"We are scientists, so we are now good at coming up with a roadmap [for] moving this all the way to the market," he says, though the team does have a "strong urge" to move the project forward.

"If we can utilize solar energy more effectively, it can give us a lot of things."

SHOW COMMENT (1)

SHOW COMMENT (1)

A huge study of TV and internet habits found that Americans get more highly partisan news from TV. Most research has focused on the internet.

Dark matter behavior may conflict with our best theory of the universe

Dark matter behavior may conflict with our best theory of the universe

World’s first carbon-eating concrete blocks are weeks away from commercial use

World’s first carbon-eating concrete blocks are weeks away from commercial useIn a first, researchers discovered a rare mineral that comes directly from Earth's lower mantle

Elon Musk picks up a fight with Apple- but why?

BlocksInform

BlocksInform